It was the middle of the night when the call from a family friend came, warning Abhishek Nautiyal and his family that they had to immediately leave their home in Joshimath, a small Himalayan mountain town in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand.

The message was simple: Get out — now.

The town was sinking after an influx of water had saturated the soil, and deep cracks had appeared in the walls of more than 800 homes, including the one Nautiyal shared with his sister and mother.

"I was very scared," said Nautiyal, now 18. His grades suffered with the constant worry during the six months he and his family moved to a temporary home, after government officials ordered hundreds of people to leave their residences, considered structurally unsafe, in early January 2023.

"This is my only hometown," Nautiyal told CBC News. "It's been hard."

Abhishek Nautiyal, 18, lives with his mother and sister in Joshimath. They were ordered to leave their home in January 2023 after it was deemed structurally unsafe by the government. They returned after six months, but their condemned house is now marked with a red X. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Abhishek Nautiyal, 18, lives with his mother and sister in Joshimath. They were ordered to leave their home in January 2023 after it was deemed structurally unsafe by the government. They returned after six months, but their condemned house is now marked with a red X. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)Studies done after the evacuation showed that Joshimath's land subsidence — the sinking of the ground surface — in late 2022 and early 2023 was intense and rapid, as high as a 5.4-centimetre drop in just 12 days’ time.

Wide fissures showed up on streets and sidewalks, as well as in homes, a local temple and two side-by-side hotels that collapsed inwards and started to lean on each other, before they had to be demolished. The town's gondola was also suspended after cracks were found in one of its towers.

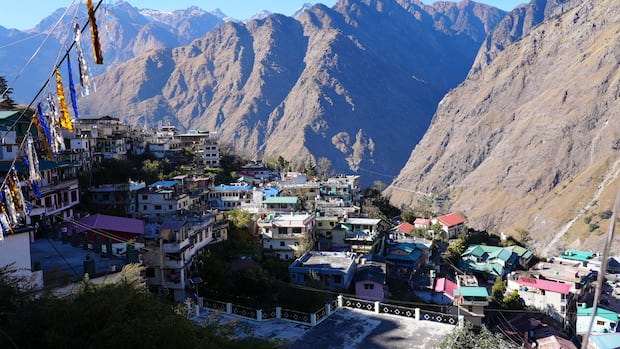

It's not a new phenomenon but the ebb and flow of life — traumatic at times for many in the hardest-hit neighbourhoods of Joshimath, a town of roughly 20,000 people in the Indian Himalayas that clings to the side of a steep mountain at an altitude of 1,874 metres.

Deep cracks are shown in the pavement in Joshimath due an influx of water saturating the soil in early 2023, causing the ground to sink. The walls of more than 800 homes were also affected. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)A recipe for disaster

Deep cracks are shown in the pavement in Joshimath due an influx of water saturating the soil in early 2023, causing the ground to sink. The walls of more than 800 homes were also affected. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)A recipe for disasterThe town is built on the debris of a receding glacier and a centuries-old landslide, which means the soil underneath is unstable and slowly, continually sinking — particularly as more people move into the area.

Experts have warned for years that aggressive and large-scale construction projects in the region, prone to earthquakes and a weak water drainage system, are making parts of Joshimath even more vulnerable to collapse.

Ice melts from the Gangotri glacier in India's Gangotri National Park, located in Uttarakhand state, in October 2022. Due to climate change, the vast majority of Himalayan glaciers are quickly receding, leaving mountain villages at risk. (Xavier Galiana/AFP/Getty Images)

Ice melts from the Gangotri glacier in India's Gangotri National Park, located in Uttarakhand state, in October 2022. Due to climate change, the vast majority of Himalayan glaciers are quickly receding, leaving mountain villages at risk. (Xavier Galiana/AFP/Getty Images)Add to that explosive mix the effects of climate change on the ecologically fragile Himalayas, the world's tallest mountain range, where temperatures are rising faster than in other mountain ranges.

The vast majority of Himalayan glaciers are receding and have shrunk 10 times faster over the past few decades than they did in the seven previous centuries. That leaves many long-established villages perched in the mountains at risk, with glacial lakes expanding and bursting in the upper Himalayas.

"It's very critical," said Manish Mehta, a glaciologist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology in Dehradun, Uttarakhand's winter capital.

"Due to climate change, the hill people are suffering from calamities like cloudbursts, flash floods and glacial lake outburst floods." (A cloudburst is a rare weather event with excessive rainfall hitting a concentrated area of 30 square kilometres or less, in a short amount of time.)

Manish Mehta is a glaciologist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology in Dehradun, a city in Uttarakhand state. He blames climate change for the 'suffering' of local residents from weather events. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Manish Mehta is a glaciologist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology in Dehradun, a city in Uttarakhand state. He blames climate change for the 'suffering' of local residents from weather events. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)In Uttarakhand, "the pattern of precipitation is changing," according to Ajay Paul, a retired seismologist based in Dehradun who knows the area well.

"There are now heavy rains and ... continuous rains," he said, and without a proper drainage system in Joshimath, "the vulnerability of the soil will increase."

A deadly flash flood in Chamoli district, near Joshimath, in February 2021 killed more than 200 people and swept away two hydroelectric projects, sounding the alarm for climate scientists studying the rapidly changing weather patterns in the Himalayas.

Heavy rains and deadly flash floods caused by glacial lake overflows battered both India and neighbouring Pakistan during this year's monsoon season — with one sudden cloudburst destroying much of Dharali, a village in Uttarakhand, killing six people.

WATCH | This Himalayan town in India is sinking:Joshimath is a small, ancient town perched deep in India’s Himalayas — and it’s sinking. CBC’s Salimah Shivji explains how climate change and major construction projects are worsening the town’s precarious situation. Damaged homes marked with a red XMore than two years after relocating temporarily, Nautiyal, his sister and their mother are still living in their house, which has an ominous red X marked on the exterior, indicating it is one of the homes that officials have ordered emptied.

They refused a government compensation package to move out of their condemned house because the amount that was offered only covered the structure and not the accompanying land.

Local officials have said roughly 40 per cent of Joshimath's population might have to be relocated if the sinking continues unabated or if there's another drastic drop similar to the one in 2023.

A woman sits next to a cracked, crumbling wall at her house in Joshimath in January 2023. Hundreds of residents in one of India's holiest Himalayan towns had to be relocated to safety after many homes, hotels and roads developed wide cracks and started sinking. (AFP/Getty Images)

A woman sits next to a cracked, crumbling wall at her house in Joshimath in January 2023. Hundreds of residents in one of India's holiest Himalayan towns had to be relocated to safety after many homes, hotels and roads developed wide cracks and started sinking. (AFP/Getty Images)"We had nothing," Nautiyal said. "No place to which we could move on and stay. We have no background support, no financial support."

The teenager dreams of passing India's notoriously difficult Joint Entrance Examination to enter engineering college and eventually move away from his crumbling childhood home.

But for now, "we have to live with it, unfortunately," Nautiyal said, pointing at the cracks in his living area.

Nautiyal's entire neighbourhood is filled with homes bearing red X marks, and many of the people still living inside them have few other options.

Almost three years after hundreds of residents were ordered to leave, Joshimath is filled with houses marked with a red X to indicate they're structurally unsafe. (Salimah/Shivji/CBC)

Almost three years after hundreds of residents were ordered to leave, Joshimath is filled with houses marked with a red X to indicate they're structurally unsafe. (Salimah/Shivji/CBC)A few doors down, Durga, 24, who goes only by one name — as is sometimes the case in India and Nepal — ran her fingers over deep crack after deep crack inside the small home she rents.

"The rains were very bad [this year]," she told CBC News. "Before, the cracks weren't as bad as right now," but the monsoon season caused them to expand.

The last place Durga and her children lived had cracks that were even worse than the ones she has to deal with now.

"We’re scared," she said, holding her five-year old son, Rehan. "If it rains heavily and something happens at night, what will we do? We have children, where will we go?"

Durga holds her five-year-old son, Rehan, as they stand in front of their house in Joshimath marked with a red X. The town is built on the debris of a receding glacier and a centuries-old landslide, which means the soil underneath is unstable and slowly sinking, particularly as more people move into the area. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)Major construction work blamed

Durga holds her five-year-old son, Rehan, as they stand in front of their house in Joshimath marked with a red X. The town is built on the debris of a receding glacier and a centuries-old landslide, which means the soil underneath is unstable and slowly sinking, particularly as more people move into the area. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)Major construction work blamedThe drone of bulldozers and construction work outside the town and elsewhere in the state continues, where a network of wider highways and railways is being built to accommodate the millions of pilgrims who travel to the area every year.

Joshimath is at the heart of a pilgrimage route for devout Hindus — with the peak, Nanda Devi, which is visible above the town, considered a manifestation of the goddess Parvati. The village is also very close to one of the most sacred Hindu shrines in the Himalayas, Badrinath Temple.

Heavy construction equipment operates near the Himalayas. Wider highways and railways are being built to accommodate the millions of Hindu pilgrims who come to the area each year. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Heavy construction equipment operates near the Himalayas. Wider highways and railways are being built to accommodate the millions of Hindu pilgrims who come to the area each year. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)Activists in the area blame aggressive construction work for exacerbating Joshimath's sinking issue, with the mountainous region serving as a hot spot for hydroelectric projects aimed at meeting India's growing need for electricity.

One such worksite, the Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower project, is about 15 kilometres from the town.

"They are building a tunnel, and that tunnel is going through underneath Joshimath," said Atul Sati, a local environmental activist. "While building the tunnel, they are using heavy blasts.”

(The government-owned public sector firm in charge of the hydroelectric project, NTPC Limited, denies its tunnel is contributing to the town's land subsidence, stating that the tunnel is more than a kilometre away and a kilometre below ground.)

Atul Sati says a government study in the 1970s recommended a blanket ban on large-scale construction work in the area, but it was 'ignored.' He and other activists blame the work for exacerbating Joshimath's sinking issue. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Atul Sati says a government study in the 1970s recommended a blanket ban on large-scale construction work in the area, but it was 'ignored.' He and other activists blame the work for exacerbating Joshimath's sinking issue. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)As early as 1976, a government study warned that Joshimath was sinking and located in an area "not suitable for a township.” The study recommended a complete ban on any heavy construction work in the area, along with a push to plant more trees, rather than cut them down.

"It was all ignored," Sati told CBC News.

That idea was underscored in an academic article titled "The Himalayas Must be Protected," published in September 2013 in the scientific journal Nature.

"Such rampant dam-building in a region with high seismic activity and fragile geology shows that the policy-makers who approve these schemes either do not understand the scientific evidence or choose to ignore it," wrote Maharaj Pandit, a leading expert on the Himalayas and a professor of environmental studies at the National University of Singapore.

Pilgrims drawn to regionOther experts don't see a way forward for the region that does not include construction in order to accommodate visitors.

"The question is: How can we mitigate the loss of life and property?" asked Paul, the retired seismologist. "What should we do? Because you cannot stop the people [from going] on pilgrimage."

Ajay Paul, a retired seismologist, says without a proper drainage system in Joshimath, 'the vulnerability of the soil will increase' because of heavier rainfall. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Ajay Paul, a retired seismologist, says without a proper drainage system in Joshimath, 'the vulnerability of the soil will increase' because of heavier rainfall. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)He suggested carefully monitoring the geological impacts of any construction project and disclosing them to the public, as well as identifying and regulating the maximum population for any vulnerable Himalayan town.

For the residents of Joshimath, scarred by constant crevices, the suggestions mean little.

Sashi Sundriyal, living in another of the houses with a red X mark, makes a pot of chai in her kitchen, keeping an eye on the deep cracks around her.

But she said she won't move out. She's not being charged rent to stay in the home and take care of it for the owners, and she can't afford to lose that perk.

"I don't think it will break [further], but if it does, I'll go elsewhere,” Sundriyal, 34, said with a shrug.

Sashi Sundriyal is shown in her kitchen, which has deep cracks in the walls, in Joshimath. Local officials have said roughly 40 per cent of the population might have to be relocated if the sinking continues or if there's another drastic drop similar to the one in 2023. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)

Sashi Sundriyal is shown in her kitchen, which has deep cracks in the walls, in Joshimath. Local officials have said roughly 40 per cent of the population might have to be relocated if the sinking continues or if there's another drastic drop similar to the one in 2023. (Salimah Shivji/CBC)The Nautiyal family is also warily observing the crevices inside their home. They have not gotten wider recently, and the family has taken pains to hide them behind paint and drawings.

"It's fine," Abhishek Nautiyal said, before adding, "I think."